January 29 - March 6, 2021

KIAH CELESTE It Is What Is Not Yet Known

“It is what is not yet known.” - Eva Hesse (1936-1970)

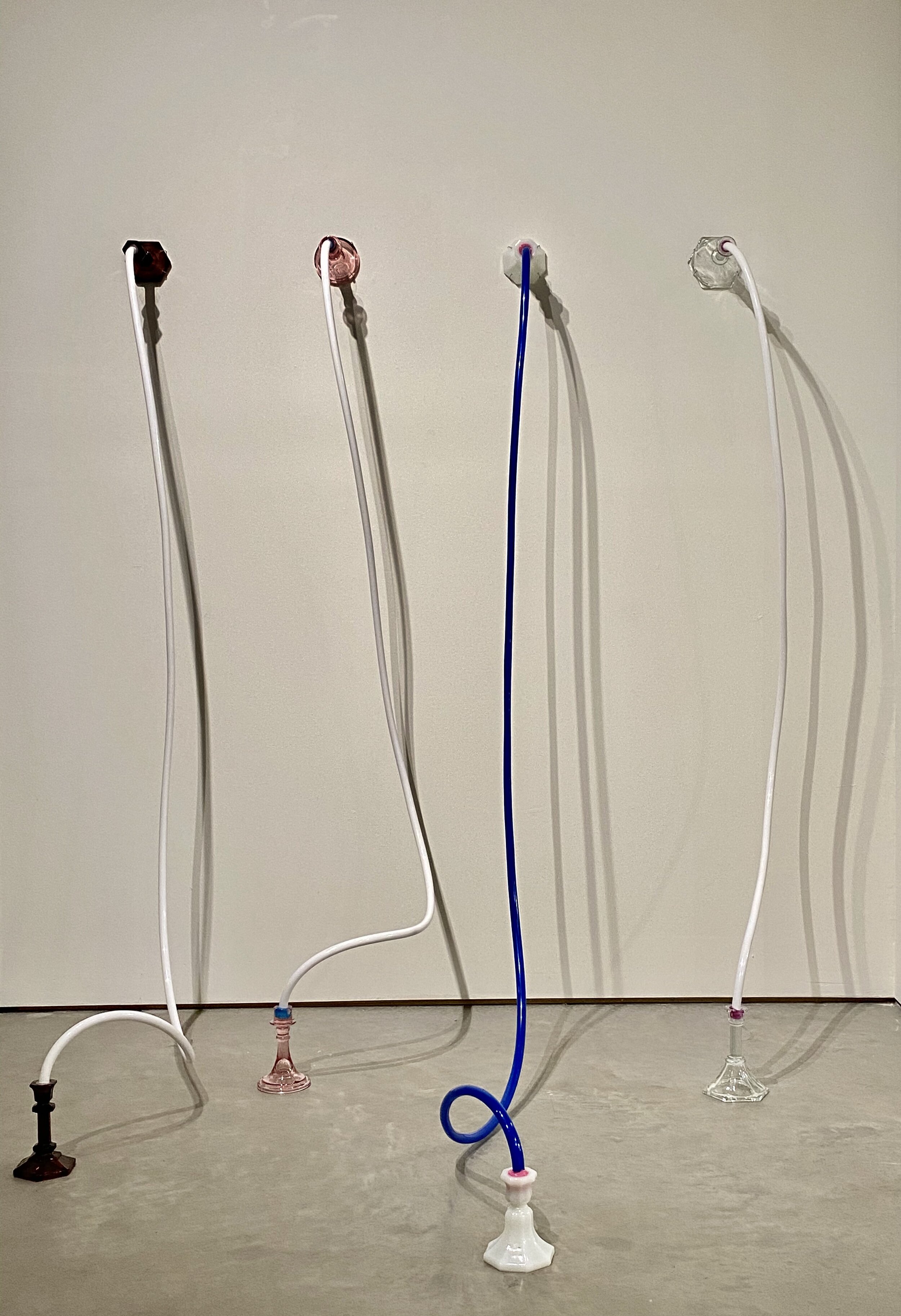

Quappi Projects is thrilled to begin our 2021 program with It is What is Not Yet Known, artist Kiah Celeste’s first solo exhibition. Over the last four years, Celeste has spent time in her native Brooklyn, Berlin, Barcelona, and Abu Dhabi, as well as her home in Louisville. This peripatetic existence, along with concerns about environmental sustainability, led to a consideration of new paths for her evolving practice, which had previously focused on photography. Celeste responded to her ever-shifting urban surroundings by scouring forgotten and remote industrial locations in search of disused materials in order to continue creating. Long interested in form and aesthetics, she began exploring the nature of and relationship between mixed materials, as well as ways to reveal their possibilities. Comprised of these discarded objects, Celeste’s resulting works are ostensibly sculptures; richly subtle and possessing an aslant beauty, they resist categorization.

Part of an ongoing series entitled “I Find This Stable,” Celeste describes these works as “not new, not young,” acknowledging that the individual components of each piece had purpose and some sort of life before being rescued from various states of entropy. Working by chance and instinct, she selects objects with an unquantifiable essence, manipulating the fragments very little. Her finished works are a testament to the fundamental importance of the individual artist’s eye: where some might see junk and detritus, Celeste sees potential and poetry. Through construction and composition, her choices change the meaning and tenor of the parts; by unifying them, she transforms them into something altogether new. Quiet attestations to notions of truth and beauty, her forms seem at once impossible and inevitable. They hold a charge of destiny, as if these disparate remnants were meant for each other—yet they aren’t didactic, they don’t brandish a narrow sort of wisdom. Celeste’s works aren’t funny, but they’re not not funny. Instead, they seem cognizant of humor, enlightened by the absurdity of their own existence and the awareness that they, like us, are subject to the whims of fate or the pull of the planets, or however any of those great existential forces operate.

Though the irony isn’t lost on her, Celeste also finds inspiration in the natural world, employing these manmade materials to mimic what she sees as its inescapable, certain—and ultimately unsurpassable—beauty. With cool restraint, each arrangement reaches equilibrium through a balancing act, resulting in combinations that hum with palpable and poetic tension. Celeste’s work also touches upon questions about abstraction and the nature of sculpture itself. Diverse influences include titans like Eva Hesse, Richard Serra, Bruce Nauman and Ettore Sottsass as well as contemporary artists like Arielle Bobb-Willis and Katie Bell. With a clear commitment to an elemental and aesthetic austerity as well as a beguiling sense of experimentation, her work shares formal affinities with that of Tony Cragg, Melvin Edwards, and Arte Povera artists whose groundbreaking and inventive material choices were situational.

Oscar Wilde famously said “all art is useless;” this quote is often taken to be an insult to all that is considered as such, but that interpretation is a misunderstanding of the nineteenth century aesthete’s intention. Wilde contended that to reduce art to questions about its function is to lose its meaning entirely. All art is inherently useless—but that isn’t to say it is pointless. Artists create because some force compels them to do so; we look at what they make because we feel a similar longing. Although it exists in the physical realm, art can also be a bridge to the transcendental, eliciting as many questions as it answers. Through her work, Celeste confirms the artist’s role in our culture as an inquisitor, an agent of otherness, a seeker of enigmatic elegance. In transforming plainly useful elements into conventionally useless things, her efforts suggest that there is pleasure and important expansion in acceding to uncertainty and the unknown. Unapologetic for their ambiguity of meaning and lack of obvious utility, Celeste’s three-dimensional assemblages feel linked to questions that haven’t yet been asked. Celebratory, sensual, Delphian, they neither resolve to justify their existence nor explain themselves; we are better for not asking them to.

- John Brooks