20 Sep—2 Nov 2019

Jacob Heustis—

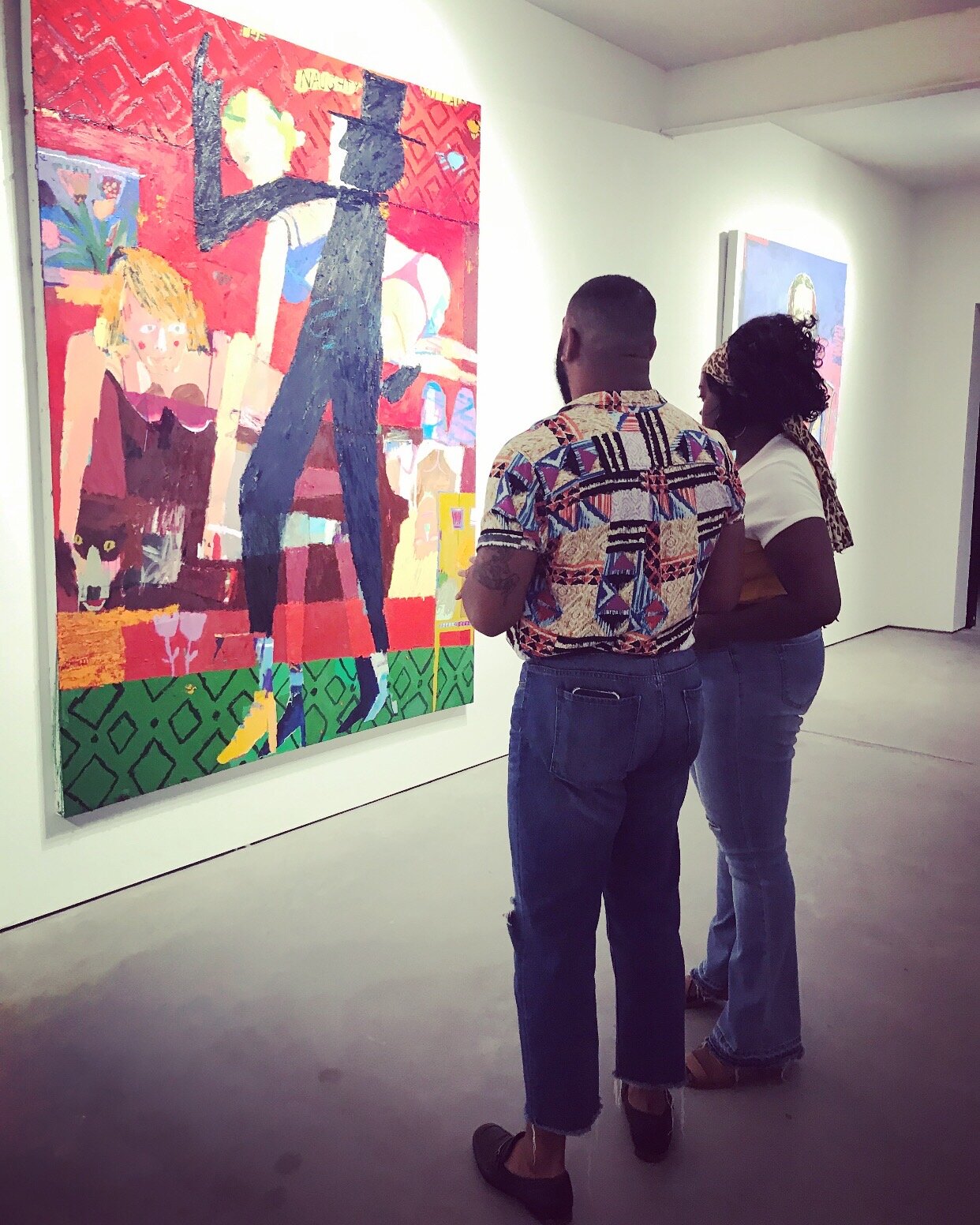

Beasts Will Be Still There

Quappi Projects presents Jacob Heustis’ Beasts Will Be Still There, the Louisville-based artist’s first solo exhibition since 2014. This new body of work finds Heustis challenging his natural minimalist inclinations. Full of cryptic imagery, pop culture and art historical references, grand in scale and complex in technique and content, these paintings befit our uncertain and discordant times. Formidable beasts, familiar icons, and mythological and symbolic figures loom in imaginary spaces just as they haunt our culture’s unconscious collective psyche. For some time Heustis has explored social hierarchy, class systems, perceptions of value, vanity and desire; those familiar themes are addressed in these new works as well as notions of faded glory, the tragic hero and its villainous opposite, and a nonchalance directed at the inevitability of our own destruction and decay.

The word beast calls to mind vivid creatures and fills us with apprehension. The 20th century was replete with beasts old and new; those beasts have followed us into the 21st. Writing in the aftermath of WWI amidst a destroyed Europe, W.B. Yeats asked in The Second Coming: “…what rough beast, its hour come round at last, / Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?” Something dreadful lurks - perhaps now more than ever. Despite centuries of progress, the old burdens - fear, avarice, lust, desire - still remain part of our daily landscape. The world Jacob Heustis presents is one reflective, even fully aware, of this distressing atmosphere. We are haunted by beasts of various origins - some of our own making and some eternal, perhaps even supernatural. The There in Heustis’ title presents a central quandary: is this a place where such beasts have chosen to dwell - a haven, perhaps, a place where they take respite from their beastly activities or is it a place where we have led them, placed them, in order to soothe and placate them? Can we rid ourselves of these psychologically manipulative beasts or must we learn to live with them or even do their bidding? The artist is a poser of questions, not an answerer, and Heustis provides no resolution, no judgment, only keen observation.

At first glance, some of Heustis’ figures may not seem quantifiable as beasts, and his discursive allusions may not seem connected, yet they are. Medusa is obviously a monster, but the Mona Lisa, the Madonna, and a parrot less so. In art historical terms, the Mona Lisa is undeniably a leviathan. Her obnoxiously outsized importance in the canon can be partly attributed to the fact that her beguiling smile represents the elusiveness of happiness, tantalizingly always just out of reach or beyond explanation. She taunts us with her secretive joy, and in Heustis’ Duchamp-referencing version, either sneers at us or with us. We are uncertain whether we are in on the joke or whether the joke is on us.

The Madonna, traditionally seen as a paragon of grace and virtue, is in Heustis’ vision imperfect, even clumsy. Human. Painted with specific references to historical Madonnas, Heustis’ Virgin is saddled with both the expectations of an infallible God and the limitations of her own humanity. She is, thus, a metaphor for all of us.

The parrot, the central figure in “No Crackers,” has an extraordinarily complex symbology. Since medieval times the bird has been used to represent the Virgin Mary - the thinking being that if the miracle of a talking animal is possible, then the possibility of a virgin birth ordained by God is conceivable. Parrots are depicted in numerous historical Madonnas, including Jan van Eyck’s Madonna with the Canon van der Paele and Albrecht Dürer’s engraving Adam and Eve. Exotic and highly prized in colonial times, parrots also came to represent desire and money; as the rare animal which can mimic human sounds and phrases, parrots also symbolize truth-telling and are witnesses to the “fall of man.” In a post-colonial age in which ideas of origin, indigenousness and reparations, not to mention proper stewardship of resources, are being widely explored, Heustis’ robust parrot as depicted in a bar-like space it appears to have claimed solely for its own kind - seems extraordinarily relevant and can be read as a rebuke of imperialism, racism, and white privilege.

Heustis is committed to making himself see and create with a learned awareness that remains unlabored and innocent. What may seem childlike is in fact anything but. “Innocence,” says Sean Scully, “is a highly evolved state that doesn’t have anything to do with childhood.” Heustis’ obvious love of and respect for paint shines; his paintings’ surfaces are highly worked yet still appear spontaneous. He makes known his knowledge of art history and gives nod to a diverse group of influences that include Guston, Hockney, Condo, Matisse, Duchamp, Beckmann, and folk artists like Bill Traylor and Howard Finster. Despite a heady subject matter, Heustis’ natural lightheartedness makes us feel that we will endure our troubles. With pithy titles and overt comedic elements, these works have a pop sensibility that speaks to the moment but they also touch on something deeper than the now, something that extends forward and backward through time. This duality compels us to keep looking, to further examine our culture and our psyches. These beasts are with us, of us, in us - and it is up to us to find ways to resolve this dilemma or quietly coexist.

—John Brooks