5.7 - 6.12

Lori Larusso

Rogue Intensities

"Rogue intensities roam the streets of the ordinary. There are all the lived, yet unassimilated, impacts of things, all the fragments of experience left hanging. Everything left unframed by the stories of what makes a life pulse at the edges of things. All the excesses and extra effects unwittingly propagated by plans and projects and routines of all kinds surge, experiment, and meander. They pull things in their wake. They incite truth claims, confusions, acceptance, endurance, tall tales, circuits of deadness and desire, dull or risky moves, and the most ordinary forms of watchfulness.”

—Kathleen Stewart, Ordinary Affects

Quappi Projects is pleased to present Rogue Intensities, Lori Larusso’s first solo exhibition in Louisville, the city in which she is now based. For more than twenty years, Larusso has been showing her paintings and installations around the United States and abroad, sharing her witty and perceptive explorations of class, gender, and culture. Through depictions of animals, foods, and food-related packaging, the work in Rogue Intensities disambiguates mundane everyday experiences while celebrating surprising, complex and surreal occurrences that take place all around us.

Largely centered around representations of food, Larusso’s practice follows a thread that began at an early age when she became fascinated with food and its sociological complexities. She developed strong ideas and associations regarding foods—which were acceptable and permissible, and which were not—growing up in the Midwest in the 1980s as a child of budget-conscious Jewish and Italian parents. Although many of us often eat without much thought, the role that food plays in our lives cannot be overstated. Without it, of course, we could not exist, but in addition to its obvious nutritional and life-giving benefits, food also has enormous societal significance. Careful examination of Larusso’s work reminds us that food and culture—even civilization itself—cannot be divorced from each other.

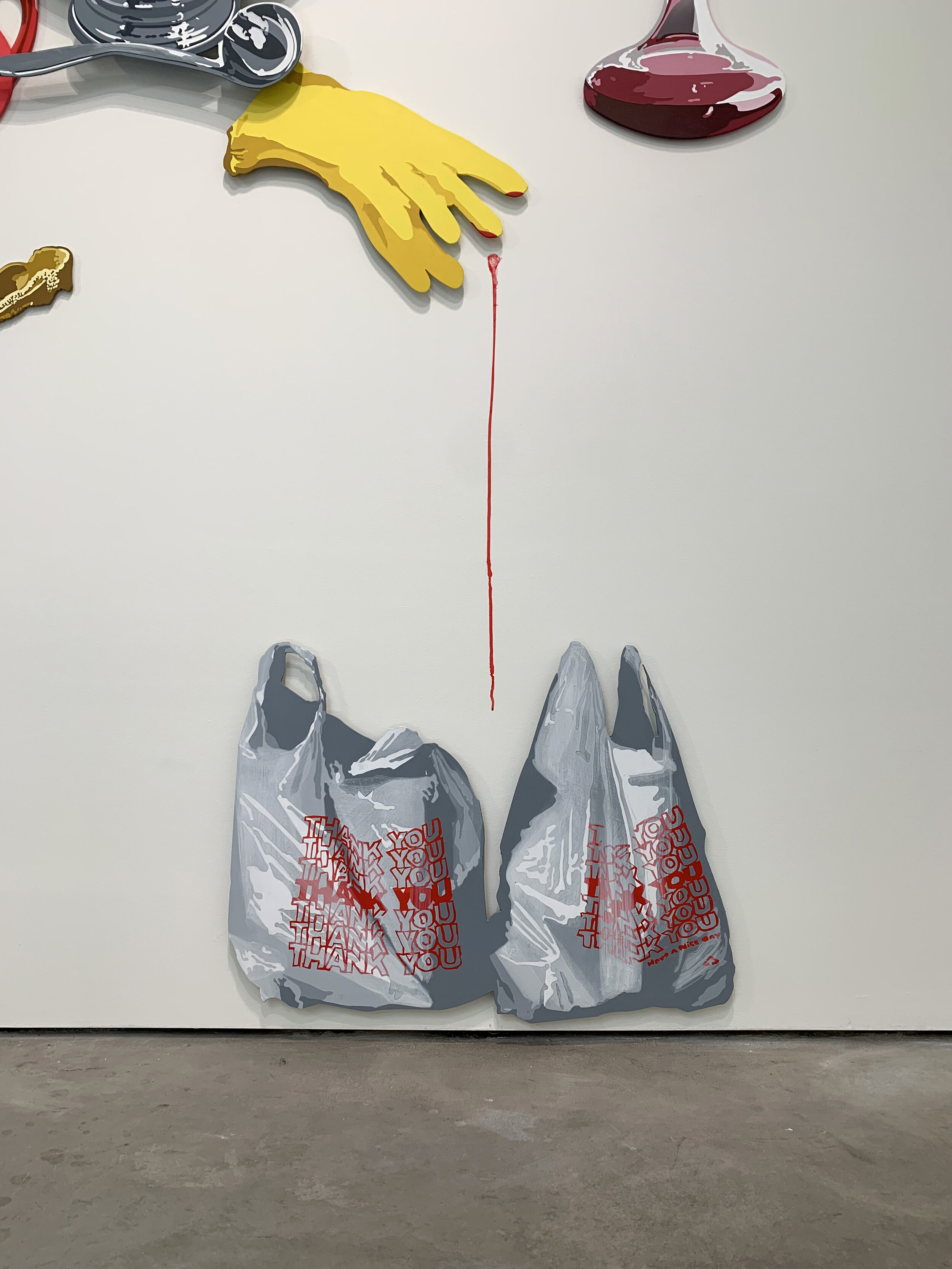

As an acknowledgement of the skills and physical effort required to produce and make food and what she describes as “the invisible labor of caregiving” in the domestic realm, Larusso cuts her metal composite or plexiglass panels by hand, then finishes them with either acrylic, enamel, or a custom self-leveling paint made for her by Golden. Flattened and simplified, her reductive images are accessible and immediately recognizable. One can’t quite taste these comestibles, as they possess some quality associated with process and product, but their formal clarity invokes a response. It is difficult to feel neutral toward these images of specific foods; more than just random amalgamations of calories, foods spur memory and arouse emotion. Keenly aware that our senses are most likely already overwhelmed by the din of every day life, Larusso nonetheless presents us with additional images, knowing that even these ersatz forms will affect us deeply.

Food as a subject in contemporary art may seem somewhat unexpected but Larusso’s true target isn’t food, it is us. Contained within or adjacent to this topic is enormous breadth: commerce, delight, delirium, desire, repulsion, as well as intricacies related to class and gender. Larusso is exploring powerful, meaningful, and timeless concepts. In focusing on this subject matter, she connects her work to a rich and long heritage throughout the history of art, from depictions in Egyptian tombs of lavish processionals of foods meant to serve as fuel for the afterlife to contemporary sculptor Kathleen Ryan’s beaded and bejeweled sculptures of rotting fruit, and many, many works of art and artists in between.

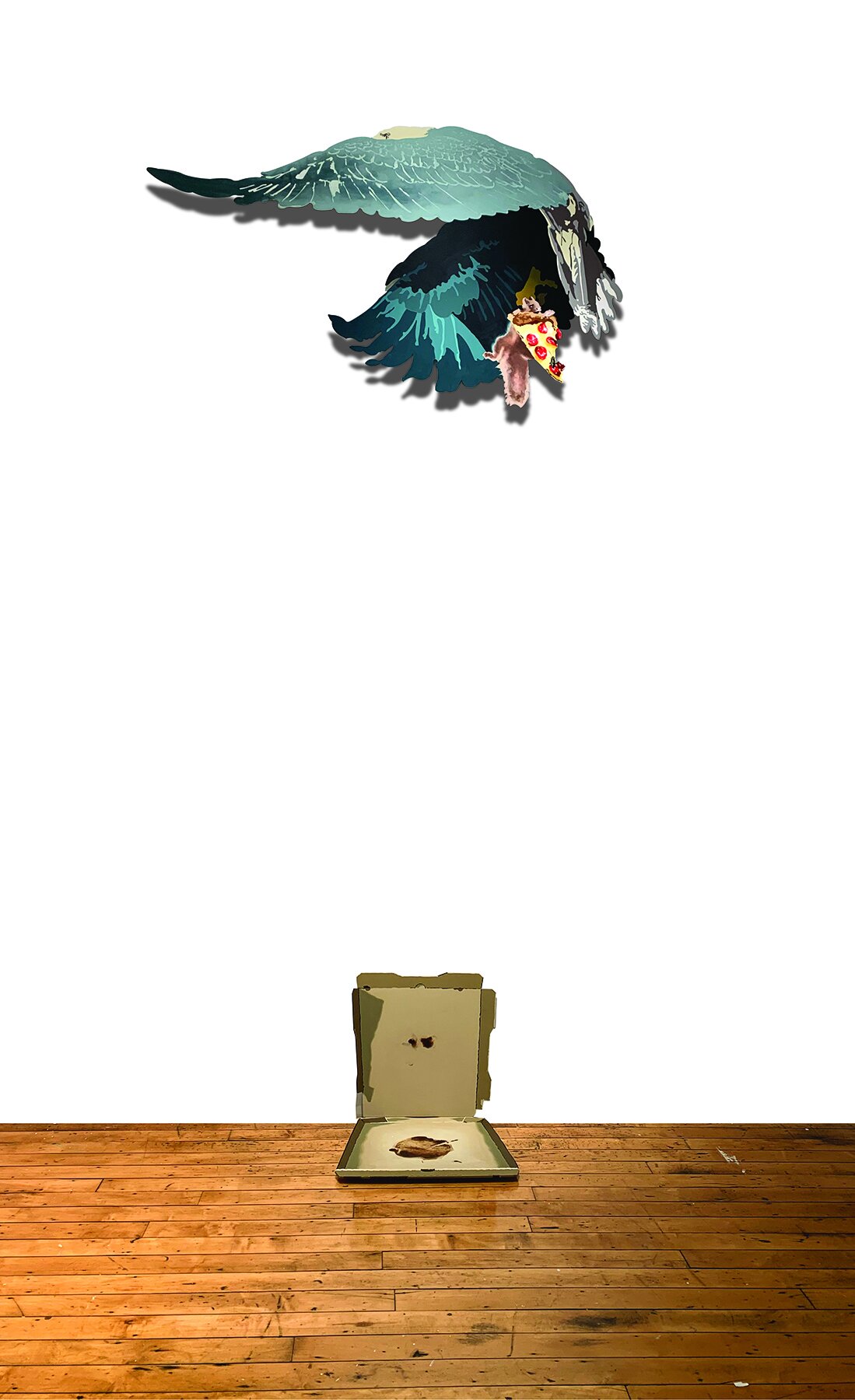

While food sustains life—or even an imagined afterlife—it often also is life, or was, in the case of animals. “I am interested,” writes Larusso, “in how we individually or collectively celebrate or condemn animals and food items—including animals that are considered foods, and foods that look like animals—based our social position, and how these attitudes are both contradictory and constantly in flux.” Larusso’s animals perform a kind of mimesis, purporting to be a thing when they are not actually that thing. This trickery is more acute in some works than others, but in each, she deftly seduces us with the familiar, anticipating our reactions; approachable and bordering on cute, these beasts call to us in a pleasant voices but closer inspection reveals more sinister themes like sacrifice, treachery, and betrayal at play. Although categorization may differ in various places, decisions that define certain species’ respective fates were made long ago and are carried from one generation to the next largely by cultural momentum. Almost invariably, human beings think of ourselves as the center of everything; Larusso asks us to step back, take a more objective view and at least consider why we do what we do, if not also consider the ethics of our behavior and customs. Nevertheless, it is clear that her view of the natural world isn’t idealized: animals, too, are driven by hunger and instinct. Larusso’s paintings are characterized by this subversive tension between images and references that seem at first to be comforting but are actually more portentous.

Of all animals, though, we humans are the most dangerous. Our appetites literally change the course of life on the planet—think of ecosystems ravaged by overfishing or rainforests clear cut for grazing cattle (not to mention the degradation of the earth caused by the lust for oil and other natural resources). With the inclusion of food packaging, some of Larusso's work becomes a kind of ecological allegory as well as a critique of capitalism, consumerism, and commodification. These single-use items begin their lives as armor that protects our food from the grime of the world before becoming garbage themselves. Elevating this cultural detritus to the status of art, these Warholian packaging pieces—which are beautiful as abstracted objects—bring attention to pressing environmental issues, reminding us that we do not exist independently from the natural world; rather, we are very much part of it and our activities—good or bad—create possibilities for new narratives. Solutions like fast food packaging promise ease, but such ease is only momentary, and the ecological imprint is on a millennial scale. This reference to time reveals that Larusso's work also has a clever relationship to Seventeenth Century Baroque and Dutch still lifes and the Vanitas genre, which often juxtaposed flowers or rotting fruit with human skulls or dwindling candles as Memento mori, reminders of life’s inherent transience and the certainty of death. As always, what dies is us; in the Anthropocene, what lasts is our rubbish.

Art lasts, too, propelling ideas, memories, and experiences into the future. The very act of making art announces that one has some kind of faith in the future. Crafting her work with precision, humor, and equal parts respect and irreverence, Larusso scrutinizes the pomp and pageantry of our food-oriented lives and the random correlating incidents that take place in the natural world. Her simulacra stimulate intriguing questions about not just image and object but also how we live. Contrasting and comparing the meaningful and the meaningless, labor and leisure, and sentience, agency, and predestination, she aims to engender a future that is no less delicious but perhaps more just.

John Brooks