12.4.20 - 1.16.21

THE SHANDS COLLECTION: NEW DIRECTIONS

curated by Julien Robson

Al Shands talks about becoming a serious collector in the early 1980s when his late wife Mary helped found and lead the Kentucky Art and Craft Foundation— what is now KMAC Museum. Beginning with works by regionally based artists, the couple subsequently began to focus on nationally and internationally known figures. As the collection developed, their interests gravitated toward sculpture and in 1986 they decided to build a new home, Great Meadows, whose architecture and grounds would provide a harmonious environment where they could enjoy and share their love of art. Since that time the collection has grown to fill the house and grounds, a place where Al regularly welcomes tours by groups of artists, museum patrons and art lovers.

He continues to collect and over the last few years his art interests have been affected by the activities of Great Meadows Foundation, his friendships with younger museum curators, and the growth of Louisville’s contemporary art scene. For him, the foundation became a rich resource to learn more about contemporary art in the state while art dealers and curators have helped him explore and appreciate new art nationally. This has resulted in an outgrowth from the collection that now goes beyond what can be seen at his home.

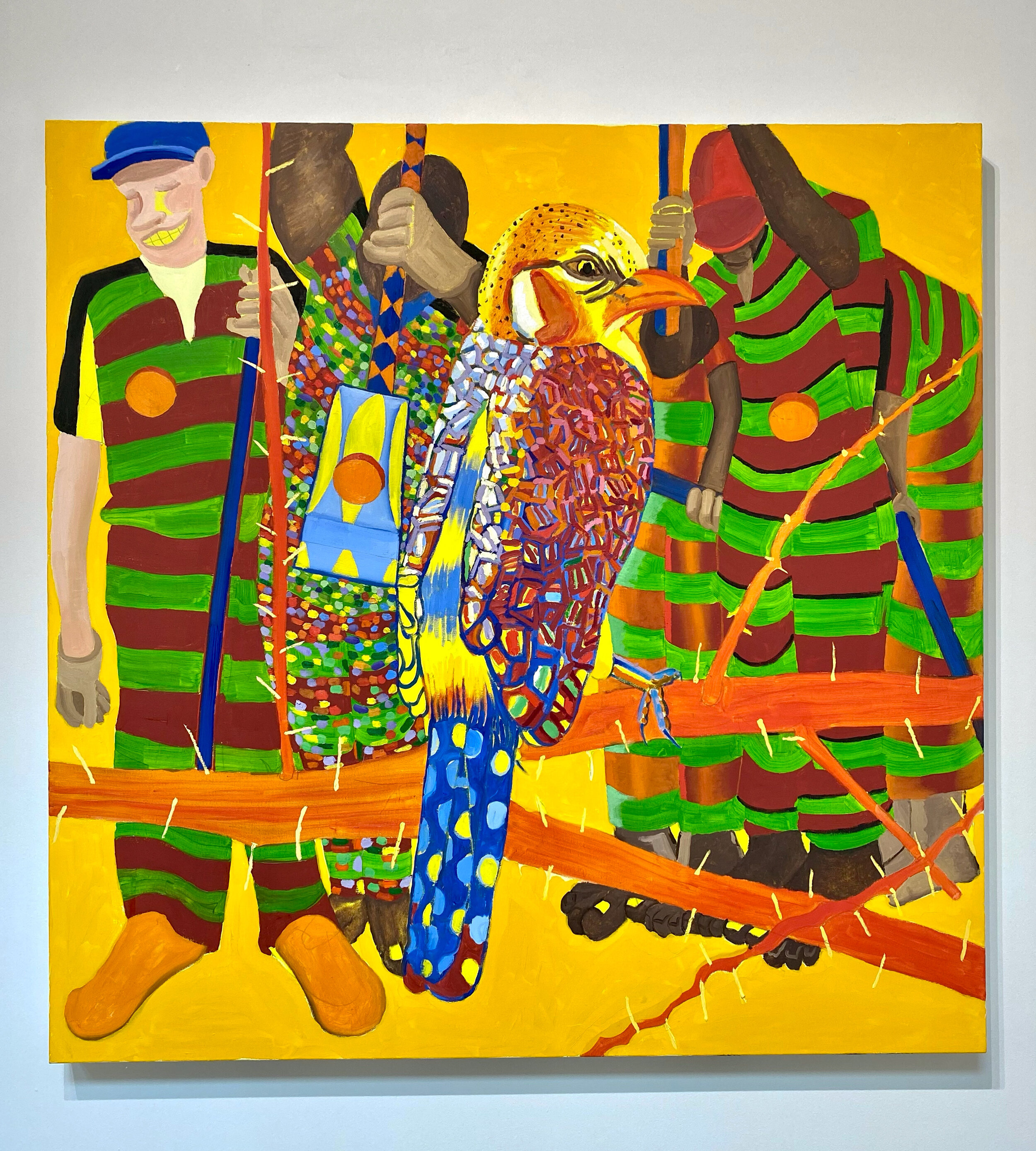

Al has always been committed to his collection being visible and, while this new collection cannot be shown in the space of his home, he has decided the works can be shared in other ways. For this purpose he envisages presenting them from time to time in curated “pop-up” exhibitions. The first of these, The Shands Collection: New Directions offers an opportunity to view works from this new collection, contextualized with works that normally reside at Al’s home. In the exhibition, recent acquisitions by Megan Bickel, Tiffany Calvert, Kiah Celeste, Rafael Domenech, Denise Furnish, Heather Jones, Letitia Quesenberry, Vian Sora, Mark Williams and Peter Williams are shown alongside works by Francesca DiMattio, Howard Hodgkin, Alyson Shotz, Sara VanDerBeek, and Mark Wallinger. It’s an exhibition that shares how this collector’s vision and mature taste continues to grow and develop as he encounters new artists. Equally, Al hopes, while giving pleasure to visitors, that the exhibition will encourage audiences to think about how collecting art can enrich their lives while supporting those creatives that make our community so culturally vibrant.

- Julien Robson

Al Shands is a human being whose mind and soul brim with questions. His biography reveals a varied list of accomplishments and interests: in addition to being an important collector of contemporary art, he founded a church, studied film, becoming a documentary filmmaker—for which he won a Peabody Award—and has written and published several books. In each of these endeavors, the common thread is his innate, intense curiosity, which Al has been able to hold on to even as he passed the age of 90. “It is,” he says, “what gets me up in the morning”—it is also the crux of what compels him to keep collecting art. This exhibition came about through a series of conversations about Al’s collecting history and habits, which are ever-evolving, and his desire to share in different ways, particularly since he has begun this new collection which exists alongside the extant collection centered around Great Meadows. While Quappi Projects is by definition a commercial art gallery not an institution, we place more value on the transformative power of art than the transactional nature of selling objects, so it feels quite natural to present this exhibition exploring the vision of one of the region’s—if not the nation’s—finest collectors.

Although he didn’t really begin seriously collecting until he was in his 40s, Al’s love affair with art began with visits to museums in Washington D.C. when he was a young man. As a teenager, he used to push his wheelchair-bound grandmother around the newly opened National Gallery. Young Al was particularly drawn to the Phillips Collection—America’s first museum of modern art, founded by Duncan Phillips in his home in 1921—by the fact that one could commune with the art mostly alone and in a domestic, rather than institutional, setting. “I felt at home in their home. That’s what gave me the idea of art as a background for where you live,” he says. Decades later, Great Meadows was designed and built to hold the growing collection being put together by Al and his late wife Mary. They chose to concentrate on contemporary art because “it didn’t look as formidable as old art. Also it was more affordable. After we married, my wife forbade me ever to buy or even look at a portrait, so we eliminated that pretty quickly,” he says. “You have to recognize your taste. Everybody doesn’t have the same taste. At my age, you know what you like. As soon as you see it, you know it.” Al has become more certain about his taste as he has aged, which is partly to do with experience, but it is also due to keen focus, which is aided by Julien Robson’s guidance and other friends and gallerists who feed him information. “A lot of people don’t collect art because they are uncertain. But you only develop certainty by doing it. You’ll make some mistakes, but that’s ok.”

This new collection was borne out of necessity. “Art has to breathe,” says Al. “I don’t like storage—the art becomes things. And so the house is full, and this new collection keeps me off the street.” He is joking, but is also quite serious. In an interview from a few years ago, Al was quoted as saying “the point of religion is to show you how to make yourself open up to change.” This beautiful, expansive notion is also the perspective from which he collects art—and perhaps more importantly why he does. In Al’s kitchen there is a framed photograph—simply grabbed off the internet—of Bruce Nauman’s famous neon work that reads: the true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths. At its best, art, like religion, can transform a life. So many people are very much afraid of that kind of language and those kind of questions. Just as art does in diluted and bastardized ways, religion plays a huge role in American culture. But it is the dogma and the certainty that generally rules, rather than the mysterious aspects. “It’s the uncertainty that is the most interesting part,” says Al. “This is partly why I like contemporary and modern art. That kind of unknowing. That’s also great in relationships. Things that you don’t know about the person that you discover as you go on. Also I am very interested in meditation, and meditation is really kind of developing a sense of awareness. But also there are so many contradictory things in our experience and I love how you can bring those contradictory things together and create a picture of life that is bigger that just what you believe in now.”

“What’s going on with this show is typical of my approach,” Al says. "To me, having a very large art collection is like having a very large dinner party. You want people that are different from each other but that can stimulate each other. You can have some bad boys that stir the pot—not too many, just a few!—and so you get bound by the limitations of the house. I think that entertaining is part of the experience of being an art collector, that you want to share it with anybody who wants to come. I suddenly realized there was a chance to start a second collection where the art has nothing to do with living with it. As long as the conversation is going on with the pieces—you don’t want something that you just can’t deal with—that’s the curiosity of it and another level of collecting. That’s what gets me up in the morning. I read the New York Times and watch the BBC with great interest in what is happening. There are people that circumstances draw you to or repel you from because things change. Change is a very important part of art, or literature, or preaching. That’s what interests me. The movement, the changes that take place. And to be able to discern what is really important within the change.”

One notable change within this new collection is a renewed focus on artists working closer to home. This is a natural outgrowth of Great Meadows Foundation, which has given travel grants to scores of regional artists and was created partially because Al wanted to spend more time visiting artists in their studios, seeing what they were making, what they were doing, and how it related to the wider conversations taking place in contemporary art. “There is great art being made in Louisville and you can learn a lot just by coming to the shows,” Al says.

A number of works from the collection have been shown in various institutions, but this is the first time any have been shown this way in a private gallery. “Being an artist is very scary business. There are no guarantees,” he says. "There are hardly any other jobs like that—people spending their lives doing something like that—and so you know that every time you buy something from a local artist everybody knows it. I’m very interested in encouraging collectors and I’m hoping this exhibition will open up the door for people to realize ‘I can do that too.’ I think one thing that really throws people off is the cost of the art. It’s so expensive. But there are so many ways to begin. You can put an expensive piece next to an inexpensive piece. Cost ultimately doesn’t matter, it’s the relationship of the works that matters.”

In terms of advice for nascent collectors, Al says that it is “a lifelong job, a very internal job, a life of discovery, what’s in you, what you like. Develop your taste early on but be very elastic about it. You have to put your toe in, then put your whole foot in. Buy something you think you can afford, something you love. Then keep looking at it. Then buy another one. And another one. And suddenly you become a collector. It becomes an obsession.”

When asked if he knew what the spark was that drew him to particular pieces over others, Al says: “I wish I knew. You can’t explain it. It’s the same thing with meeting people. I think of the works as personalities. You have an intuitive feeling. I am looking for depth, and things that look too easy make me suspicious. I am interested in pieces where the artist makes you dig some; you can’t solve this logically. You have to let things sit, and you keep thinking about this piece. Also, something that has always interested me is elegance. Being able to spot elegance. In literature, poetry, art, music, everything. You don’t find a lot of it in modern society. You have to look for it, but it is there. It has always intrigued me from my earliest days that I can remember. And I had a kind of way of spotting it. I like art that attracts you with almost one note. It’s one thing that’s very clear. It’s very focused. There can be other things around it that are less focused, but you have to be able to immediately connect and say ‘Yeah, I see what the artist was trying to do here.’ Or you see what you see. Although Julien has helped me to see that what I see is not necessarily what the artist thought.” He laughs a little. “Does that matter?” I ask. “The thing is…I am near the end of my life. Does anything matter? We are all part of a flow. Some of us are coming, some of us are going.”

Whether in the quietude of his home, a gallery or museum, or in a holy sanctuary, Al is fulfilled and enthused by contemplation. A philosophy that accommodates such willing doubt and allows for such deep humility and presentness makes a magnificent blueprint not just for collecting art but also for living a life.

- John Brooks