7 August - 12 September

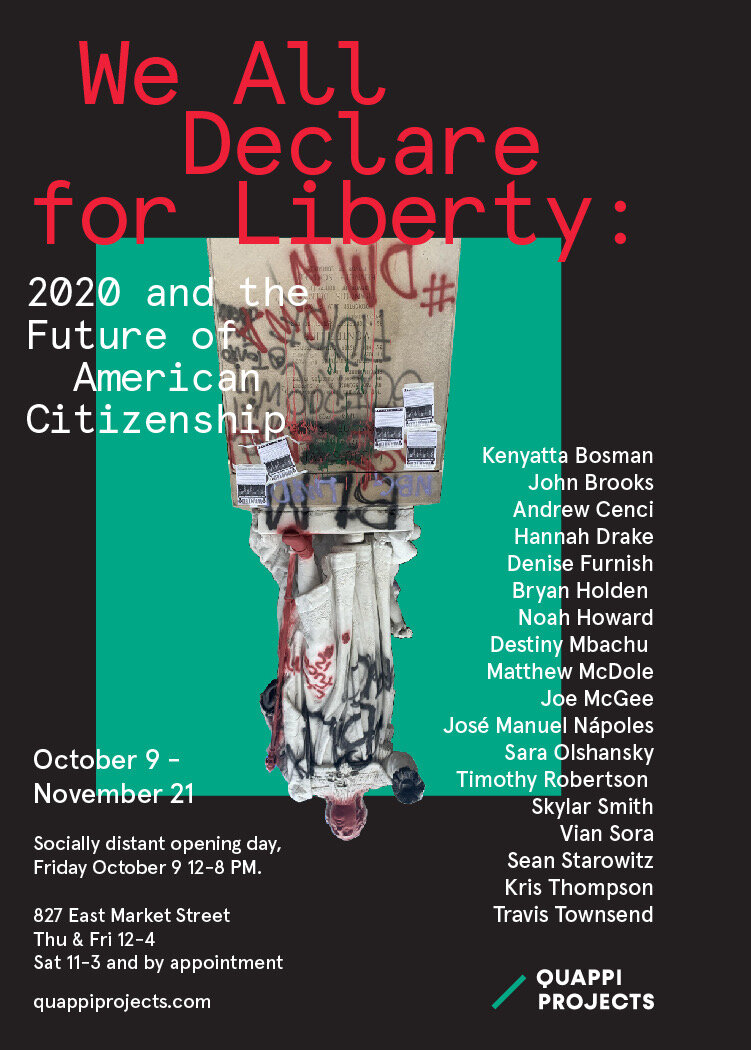

We All Declare for Liberty: 2020 and the Future of American Citizenship

Kenyatta Bosman

John Brooks

Andrew Cenci

Hannah Drake

Denise Furnish

Bryan Holden

Noah Howard

Destiny Mbachu

Matthew McDole

Joe McGee

José Manuel Nápoles

Sara Olshansky

Timothy Robertson

Skylar Smith

Vian Sora

Sean Starowitz

Kris Thompson

Travis Townsend

“The world has never had a good definition of liberty, and the American people, just now, are much in need of one. We all declare for liberty; but in using the same word we do not all mean the same thing.

With some the word liberty may mean for each man to do as he pleases with himself, and the product of his labor; while with others the same word may mean for some men to do as they please with other men, and the product of other men’s labor. Here are two, not only different, but incompatible things, called by the same name — liberty. And it follows that each of the things is, by the respective parties, called by two different and incompatible names — liberty and tyranny.”

- Abraham Lincoln, 1864

Although President Lincoln was speaking specifically of diverging definitions by those who were for and against slavery, the critique of our national discord is still apt, perhaps more so now than at any time since the Civil War. Ours is a time in which opposing political factions disagree not only about policy and the purpose and function of government but also something as basic as facts. How can our nation endure and remain unified in an environment rife with such rancor, overt gaslighting and threats of a new civil war, particularly when certain actors seemingly welcome, even stoke, the fires of division? Through a process of an open call and invitations, Quappi Projects has brought together a diverse group of artists whose thoughtful, complex works aim to elucidate the state of our national politics and its future, as well as the future of American citizenship - what defines it, who it belongs to, and what it requires of us.

With its stylized forms, clean lines, wry sense of humor, and references from pop and skater culture, the work of Matthew McDole is immediately recognizable. Infinite Jest is his satirical indictment of American-style capitalism and contemporary American life. The piece borrows its title from David Foster Wallace’s 1996 novel of the same name in which the United States, Canada and Mexico comprise a unified North American superstate known as known as the Organization of North American Nations (O.N.A.N.) where corporations have found a way to further monetize time by bidding for the naming rights of each calendar year. Speciously sunny, McDole’s vignettes read like advertising blurbs for opportunist companies and products desirous to take advantage of the feelings of desperation and resignation with which so many Americans have become familiar. As we witness the literal and figurative structures of our society crack and crumble, the marketing doesn’t cease: yes, things are bad, but you might as well buy and sell - that’s the American way! But in McDole’s view, we are not in control of this commerce. It seems that the product is us.

Kenyatta Bosman’s KING LOUI was taken on the streets of downtown Louisville in the early days of the Breonna Taylor protests this summer. Bosman, a twenty-six year old non-binary photographer whose work depicts the Queer Black experience, has been deeply involved in the protests and racial justice movement in their native city. Their work always possesses a sense of drama. KING LOUI deftly captures the atmosphere of the moment: frustration, despair, anger, pride, and an easy defiance are all palpably present in this group of young protestors. They seem to have found connectedness and kinship in the shared experience of exercising their Constitutional rights. The image’s central figure, who could easily be Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice or perhaps Bosman themself, rides a bicycle while wearing a hoodie that reads “KING a king of oneself.” Exuding a calm resoluteness, he leads the group onward, the wheels of his bike breaking the confines of the frame.

Sean Starowitz’s work has been concerned with social practice and social discourse for more than a decade. statues are silent teachers was conceived and created in direct response to this exhibition’s prompt. He writes: “my work straddles the line between imagined destruction and the exploration of something beautiful that can come out of reimagining memorials, monuments, and public grounds/spaces. Beauty is hardly a feeling that represents the trauma involved in our history and the subsequent reimagining of such spaces. I do believe that destructive actions are necessary and things being broken can bring closure. Spolia (Latin for spoils) is an ancient practice that carried symbolic and spiritual value. Builders would lay a statue on its side in order to place it and the power it represents under control. This way of repurposing building stone and or decorative sculpture was a widespread practice in the creation of new monuments, buildings, and memorials.”

This monument, made of Indiana limestone - which itself is comprised of the remnants of 300 million year old seashells, from a time when our region was at the bottom of a primordial sea - is a proposal for a monument for the National Garden of American Heroes, taken from the Executive Order on Building and Rebuilding Monuments to American Heroes, signed by President Trump on July 3, 2020. Starowitz knows his proposal would be rejected by Trump administration officials because the Executive Order states that “all statues in the National Garden should be lifelike or realistic representations of the persons they depict, not abstract or modernist representations.” There is much to pick apart here, not least the absurdity of an obelisk being rejected for being “abstract or modernist.” A powerful symbol originally meant to represent a petrified ray of sun, the obelisk - called tekhenu by their builders - dates back thousands of years to ancient Egypt. It is also one of our most easily recognized national symbols. The ideas behind “abstract and modernist” art are now at least a century old - hardly new; the Trump administration’s wholesale rejection of them is reminiscent of the Nazis’ rejection of what they termed Degenerate Art (Enartete Kunst). In 1937, after confiscating an untold number of contemporary artworks, the Nazis put on a series of exhibitions meant to mock art and artists whose ideas they deemed radical. In a speech that summer, Adolf Hitler said “works of art which cannot be understood in themselves but need some pretentious instruction book to justify their existence will never again find their way to the German people”. Time and time again it seems that complex thought is the enemy of autocrats; a citizenry that thinks for itself is dangerous to those who wish to aggrandize power.

Starowitz’s monument is a mirror to the current state of affairs: due to a disinterested and incompetent federal response, over 207,000 American lives have been lost to COVID-19; tens of thousands of citizens in cities and towns across the country have gathered together to protest police brutality against black people and an unjust system that does not serves them. Starowitz contends that the federal government seems more interested in protecting things rather than people, writing: “this summer, the Trump administration released an Executive Order on “Protecting American Monuments, Memorials, and Statues and Combating Recent Criminal Violence,” which allows the federal government to prosecute to the fullest extent permitted under Federal law any person or any entity that destroys, damages, vandalizes, or desecrates a monument, memorial, or statue within the United States. Against the backdrop of a 100-year global pandemic and the restructuring and revising of our public memory and spaces in many communities across the US, this distinct set of executive orders are not just passive declarations or empty promises of a politician. These are doctrines for white supremacists ideologies to redefine the meaning of citizenship and identity in the built environment.”

I chose to include my own work in this exhibition because this topic is so important to me and central to my practice. Person, Woman, Man, TV, Camera utilizes screenshots of a 1953 episode of “What’s My Line” featuring mystery guest Eleanor Roosevelt, former First Lady and United States Delegate to the United Nations General Assembly. Asking a series of questions, the panelists - in this episode Bennett Cerf and Dorothy Kilgallen (who later died under mysterious circumstances perhaps related to the assassinations of JFK and Jack Ruby) - would attempt to determine the identity or occupation of the guest. In the case of famous guests, the panelists would don masks to further confuse them, and sometimes the guests would not even answer in their own voices if they were well known. I watched this episode earlier this spring and felt that the image of willfully blinded inquisitors seemed a great metaphor for our currently distracted and / or willfully ignorant citizenry. In an era of “fake news” and “alternative facts,” so many seem so willing to ignore obvious truths, and to ignore the power of their senses. Additionally, Mrs. Roosevelt’s incredible accomplishments and graceful earnestness contrast so sharply with the particulars of many currently in what used to be called public service. The answers to a better future are quite obvious except to those who refuse to see. To remain on the current path, willfully blinded, is to sink further into a the neon chaos of this Twilight Zone game show we are in, where he who can remember “person, woman, man, TV, camera” is to be given the highest praise and the reigns of power.

Born in Baghdad, Iraq, Vian Sora spent her childhood and youth living under the cruel regime of Saddam Hussein. Her family suffered immeasurably and in ways irreversible under his terror. War and terror continued to dominate Sora’s young adulthood when the U.S. invaded Iraq in the aftermath of 9/11; car bombs, kidnappings, and killing machines were a part of daily life. Sora will tell you that she is tired of telling this story but that its shadow is inescapable. It is the story of her life. Having married an American, Sora emigrated to the U.S. in 2009 and became a citizen in 2013, a process that took seven years. Over the last several years, her elderly parents, who were essentially stateless living elsewhere in the Middle East, emigrated here as well. After an arduous process, they finally received their Green Cards. Sora’s lone sister has also come to join her family in Kentucky but has been denied refugee status. An appeal is ongoing. It is partially her sister’s distressing experience with U.S. immigration officials that Sora depicts in Babylon to Babel. An abstracted and splintered American flag is recognizable as it envelops figures involved in some exchange. A Babylonian lion - a symbol of ancient Iraq - represents Sora’s sister but also Sora herself, her family, and others like her who have come to this country in search of a better life only to be met with hardships, prejudices, and hatred. It is not that life in the U.S. is all bad - there are many wonderful things about her chosen country - but Sora’s home country was left in absolute disarray after the U.S. invaded and life here has been much more difficult over the last few years as first candidate Trump and now President Trump and others engaged in open xenophobia. As in most of Sora’s recent work, the imagery functions on various planes: the figures give way to what appear to be aerial maps, as if seen from bombers, under which are buried organs and body parts of victims of war. Featuring close ups of two figures, Denizens is a companion piece to the painting.

Vian Sora appears courtesy of Moremen Gallery.

As a man who builds things, Travis Townsend thinks about the things that men have built. Are they good? Is what he has built good? What have we done with our time, with our hands? We look around us and take what we see as a given, but excluding the natural world, everything has been built by us and is a result of a series of choices and decisions. Some essential needs of humankind necessitate building, but our reasons for doing so are much more complex, even innate. In a way, that which we choose to build are our desires made material. Like our own built environment, Townsend’s ark-like vessels are sketched, built, carved, cut up, drawn upon, tinkered with, assembled, disassembled, reassembled. Sometimes the process takes more than a decade; perhaps it is never finished. With its off-kilter slant, Vessel of Manifest Destiny! (2nd Permutation) rests inert, like an earnest but useless relic from a forgotten land. Or could it also represent our own nation which, from its beginnings, has been cobbled together from various parts and peoples and is still evolving? Manifest Destiny - the imperialist idea that the United States was ordained by God to expand its ideals and dominion across the continent - has long been part of our culture and used to justify so much, including genocide. Townsend says that “we live with the consequences of our collective brutal humanity.” Though we tell ourselves that the phrase and the ideas it represents are no longer part of us, we have continued “nation building” in this century. And just this past January, President Trump in his State of the Union address said “In reaffirming our heritage as a free nation, we must remember that America has always been a frontier nation. Now we must embrace the next frontier: America’s manifest destiny in the stars.” What is it that calls us to the heavens - a desire to explore or a desire to conquer? The difference matters. Before we annex outer space, we should ask ourselves whether or not we have been good stewards of this planet. And if the answer is no, should we not get busy building a better world here?

Bombarded with images, symbols, and messages, we are drowning in media. Our built environment, human made surroundings, and the influence of imagery has profound impact on each of us and on our culture as a whole. Artist, instructor and curator Timothy Robertson asks “how much does our view of what the future of American citizenship holds depend on our physical environment? How do the symbols created and manipulated in our environments determine the language through which we share our visions for the future?” North, South, East and West, depict an American flag casually draped atop a wheeled garbage bin - a scene Robertson happened upon, causing him to wonder: “is it a statement, a gesture of honor, or an unintentional pragmatic motion? Our physical surroundings are not just a product of location but also of socioeconomic status, racial and ethnic backgrounds, migrations, invasions, occupations.” Though we often presume symbols have universal meaning, this isn’t true. Our interpretation of any symbol is dependent upon our identity, experiences, and filters. Robertson says “the physical environment informs and distorts our language; it shapes the shadows the symbols of our citizenship make.” How much control do we have over the symbols we use and what they mean?

Skylar Smith writes that A History of Women’s Suffrage “charts the dates women were granted the right to vote in 196 countries around the world. Each country’s name and year(s) of women’s suffrage were painted, wiped away, and repainted to create a palimpsest that represents the historical assertion of the female vote, and simultaneously the absence of the vote and female political leadership. The layering of this information also points to the arbitrary nature of these dates, which were often conditional according to race, education, and property ownership.” Take note of a few dates - Saudi Arabia 2015; Switzerland 1971. The U.S. has a series of dates because voting rights, like most rights in this supposed “land of the free,” have been doled out conditionally. Smith’s United States, 1870, 1920, 1924, 1943, 1965 explores this further. 2020 is the centennial of the 19th amendment, which granted women in the United States the right to vote, but that was only true for white women, not all women. Native American women were not granted the vote until 1924, Asian American women could not vote until 1943 and it wasn’t until 1965 that most African Americans could vote in the Jim Crow south. In a democracy like ours, there is no greater right than being able to participate in choosing one’s representatives in government by voting, yet for too long and for too many people, those in power - and, it must be said, some fellow citizens - have pretended that voting is a privilege that must be earned rather than an automatic birthright guaranteed to all. Even now there are elected officials aiming to limit both citizens’ access to voting and the number of voters. What kind of government - and thus what kind of laws - would we have if women and other minorities had been granted the vote all along? What form would our nation take if every leader and every party did all they could do to ensure that voting was simple, fair, accessible, and absolutely encouraged?

The intransigent state of our politics is the catalyst for Sara Olshansky’s say it too many times: Lose Your Voice. To make one’s opinion known or to be visible in the public sphere is still seen as a political act. This layered self-portrait uses repetition as a metaphor for the frustratingly necessary redundancy of continually having to speak up and claim one’s rights as a woman, particularly in a state like Kentucky where “trends in voting do not reflect (her) beliefs, where resultant policies directly affect (her) autonomy.”

If calls for change are repeated ad infinitum they can lose their charge of urgency, yet they are still needed. Despite some progress and the fact that we are well into the twenty-first century, Olshansky wonders if in her lifetime she will ever see a woman or a Jewish person like her as president. Employing erasure as addition, Olshansky obscures herself within herself, her voice and her person enmeshed in an echo chamber, unsure if she is being heard - or worse, unsure if she is being heard but is being disregarded. The ghostly figures also represent other citizens invisible to those in positions of power, desperate to be seen and aided by the very people who ignore them.

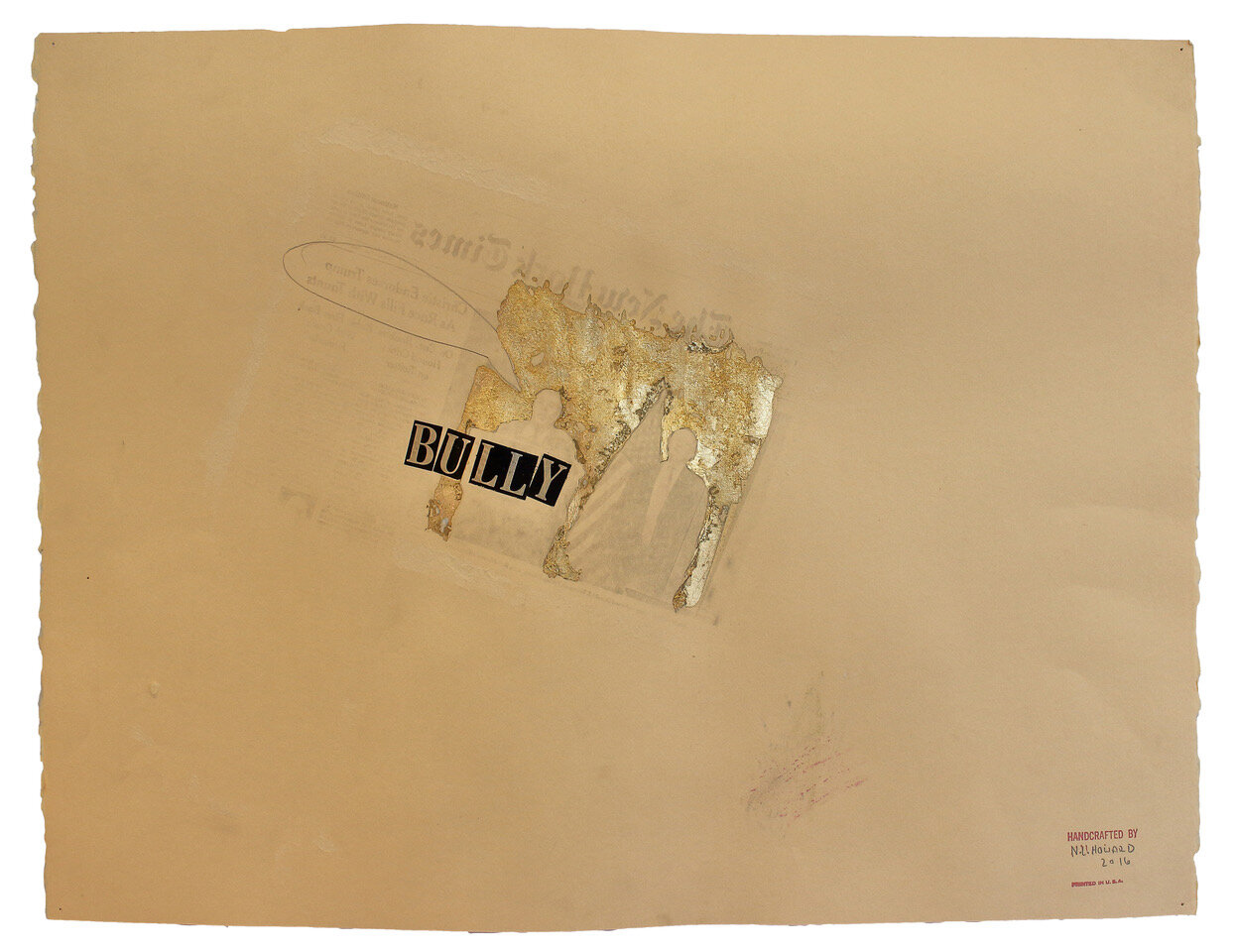

Completed during the 2016 campaign, Noah Howard’s LEST (DON’T VOTE FOR FUCKERS LEST YOU’RE LOOKING TO GET FUCKED) is a jeremiad about all that is Donald Trump and Trumpism. Howard was baffled and saddened as he watched this known charlatan rise to a place of political prominence and ultimately the Presidency - the highest office in our nation - by engaging in an unending avalanche of fear-mongering, lies, half-truths, insults, and threats. Howard has employed imitation gold leaf as a metaphor for both Trump’s falseness and the way we arbitrarily and subjectively assign value to things and materials. The ensuing three-plus years under Trump’s control have been anything but normal - we have all been living in a reality of his making as norms, expectations, and even the rule of law have been bent, if not broken, to satisfy his demands. As Howard says, “the larger Trump’s field has become, the greater the toll on humanity, as now most people on this planet have been touched by his weaponized communications.” But no one, not even Trump, exists in a vacuum; Trump’s behavior, positions, and attitude do reflect those of not just a few citizens. He is a product and representation of our culture, but also of human nature itself. There have always been demagogues, and there have always been people willing, even hungry, to follow them. Where do we go from here? It is impossible to look at the state of our nation and contend that we are more unified or that we are happier than we were four year years ago. The tension is palpable. Will our “leaders” continue to divide us, or will we reject virulent tribalism and remember and honor the original motto of our nation: E pluribus unum?

José Manuel Nápoles’ desperate waiting and happy endings tells a story of immigration both personal and universal. A native of Cuba, Nápoles left his home country and traveled through eleven countries in order to emigrate to the United States. Like so many others who have come here in search of a better life, his was a journey of hardships and determination. Nápoles says his simple figures are “protagonists of an emotional exorcism” and that they “refer to childrens’ iconographies to discuss emotions, moods.” The painting is a portrait of his fiancé Maria, also a Cuban native who came to the United States in search of freedom. Ours is undeniably a nation of immigrants, yet in recent memory they have been demonized by many politicians and some in the media. Drawing on his lived experience, which includes brutality and fear, Nápoles brings a visceral humanity to the abstract notion of who or what is an immigrant. Though not yet a citizen, Nápoles says “I am so grateful to have been generously given freedom in this country and I will do the impossible to be a citizen worthy of my second homeland.” In our relative comfort, it is easy to take for granted how good we have it; Nápoles’ tenacity should jolt us all out of complacency.

Destiny Mbachu describes herself as a photographer, model, writer and cultural curator. Along with her artistic partner Bearykah Badu, she recently founded A Well Written Photograph, “an original Black collective aimed at promoting Black artistry and Black creativity through community outreach.” Mbachu’s practice is lifestyle-related, closely aligned with aesthetics, fashion and body positivity. At first glance, her selfie SHOW ME SOME FUCKIN RESPECT may not seem particularly political, but it can be viewed as the physical embodiment of the ideas expressed by Hannah Drake’s poem Spaces. Mbachu’s confident gaze says it all: I’m here, I’m beautiful, this space is mine, and I will not be denied. Not every act that has political or social effect will be explicitly or obviously political; there is more to being a citizen than just stepping into a voting booth. The everyday practice of claiming space is absolutely necessary in order to create more visibility, opportunity, and a more just society for Black people and other minorities.

Consume, constructed with found objects such as plastic liquor bottles, cardboard signs purchased from homeless people, cigarette butts, pills, syringes, keys, a wedding ring and various materials, is sculptor Bryan Kelly Holden’s tribute to those who have overcome addiction. Through a combination of self-determination, faith, and community support, Holden believes it is possible to learn to control chemical dependency. Circumstances for many are particularly difficult in 2020; this year has wrought devastating economic realities for tens of millions of Americans, many of whom have turned to alcohol, drugs and other things as sources of escape. With no end currently in sight to either the economic downturn or the COVID-19 pandemic, what does our collective future look like? Can enough of us hold it together to make it through to better days, and can those same people be a source of strength for others who are struggling?

Kris Thompson, a fiber artist who designed her own L.A.-based label and whose recent work has been focused on creating wearable art for KMAC Couture "Art Walks The Runway" held at KMAC Museum, fears a future where her rights and the rights of other women are restricted by men. MAGA takes direct inspiration from Margaret Atwood’s 1985 dystopian novel (and subsequent Hulu series) The Handmaid’s Tale with an update for the MAGA (Make America Great Again) age. In Atwood’s novel, set in an unspecified near-future, the United States as we know it has been overthrown by a totalitarian, uber-patriarchal regime called Gilead. Women, particularly women who are not married to powerful men, have few if any rights and are subjugated by the strictures of men and an extremely rigid religious fundamentalism. In Atwood’s story, worldwide birthrates have plunged and in Gilead, fertile women are rounded up and forced to be Handmaids - essentially sex slaves - in order to bear children for their owners, known as Commanders. Handmaids are also required to wear uniforms that include bonnets; over time, as more women revolt, the uniforms are given a horrifying update that covers the mouth. It is a brutal society, and one that might seem far-fetched, but Atwood (and the show’s writers) took inspiration from real-life regimes and groups around the world that continue to oppress women.

In our own country, women continue to fight for equal rights, equal pay, and autonomy over their own bodies and medical care. Though he later backtracked, candidate Trump said in March 2016 that abortion should be illegal and that “there has to be some form of punishment” for women who have abortions. As President he has, with wide Republican support, espoused a desire to see the Supreme Court overturn the landmark 1973 abortion-rights case Roe v Wade, recently saying that “it is certainly possible” if his nominee Amy Coney Barrett is confirmed to replace the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg. How can the rights of so many be existent or nonexistent based on the opinion of one woman, or even a portion of nine Justices? In an absurdist twist, Barrett is a member of a charismatic Catholic group known as People of Praise that teaches, among other things, that men have authority over their wives. According to a 1986 interview, this was one of the fundamentalist groups that originally inspired Atwood to write her novel. Members of People of Praise are assigned to personal advisers of the same sex—called a "head" for men and "handmaid" for women. After the novel’s success, People of Praise began calling “handmaids” “women leaders.” Thompson’s work asks, in Trump’s twenty-first century America, can this be where we are headed?

Louisville-based photographer Andrew Cenci captures everyday events and candid occurrences. When they began this summer, Cenci, who is African-American, felt compelled to participate in and document the Breonna Taylor protests (which are ongoing). Like any event where large numbers of people gather, protests can be loud, boisterous, and chaotic, yet there are also small, quiet, profound moments. These go unnoticed by most. The two images here, Sing About Me and I’m Dying of Thirst, highlight Cenci’s sensitive and poetic eye. His chosen moments feel intimate, individual. With an adroit focus on stillness, Cenci reminds us that ours is a time of change, as well as a time for reflection, and that both are essential. Also essential to this exhibition is the presence of Breonna Taylor, both in name an in image. Cenci’s photographs are elegies to her memory.

The United States was built on the backs of enslaved people like York (1770s - before 1832), who was considered the property of William Clark. In 1803, Clark, who was living on his family’s plantation here in Louisville, and Meriwether Lewis led the famous Lewis and Clark Expedition to explore the western half of our nation. As Clark’s slave, York accompanied the two white men and was absolutely vital to the success of the harrowing journey into the wild and unknown. Clark promised York his freedom upon the completion of the journey but did not honor his word. Only ten years after the expedition did Clark finally release York from enslavement. In Joe McGee’s William Clark's Slave York is Denied His Freedom, 1806, York has returned to Louisville and realizes that nothing has changed. Despite being the first African-American to have crossed North America to reach the Pacific, he is still an enslaved human being. McGee is an artist whose work touches on the sublime and is charged with a spiritual currency. The stories he tells are not necessarily his own, but are an attempt to commune with others on a higher plane. In this work, York is monumental; his strength of mind and body is evident. The keelboat on which the three explorers traveled appears ready to impale his arm, inflicting further damage on a man who was denied his humanity all his life. McGee has depicted York atop discarded Kentucky Tourism Reproductions showing Mammoth Cave and the Ohio River as a way to tell us that York is still here with us. York’s story is one of many; countless enslaved Africans and their descendants lived and died so that our young nation could prosper. We have never honored them as they deserve. We have never properly dealt with this sin and its repercussions continue to haunt us. With racial justice now on the minds of so many of us, will this moment of righteous indignation finally lead to some kind of reparations and real healing? Or will we find a new way to pretend that we have fixed this issue or that it doesn’t matter? Our future depends on right actions.

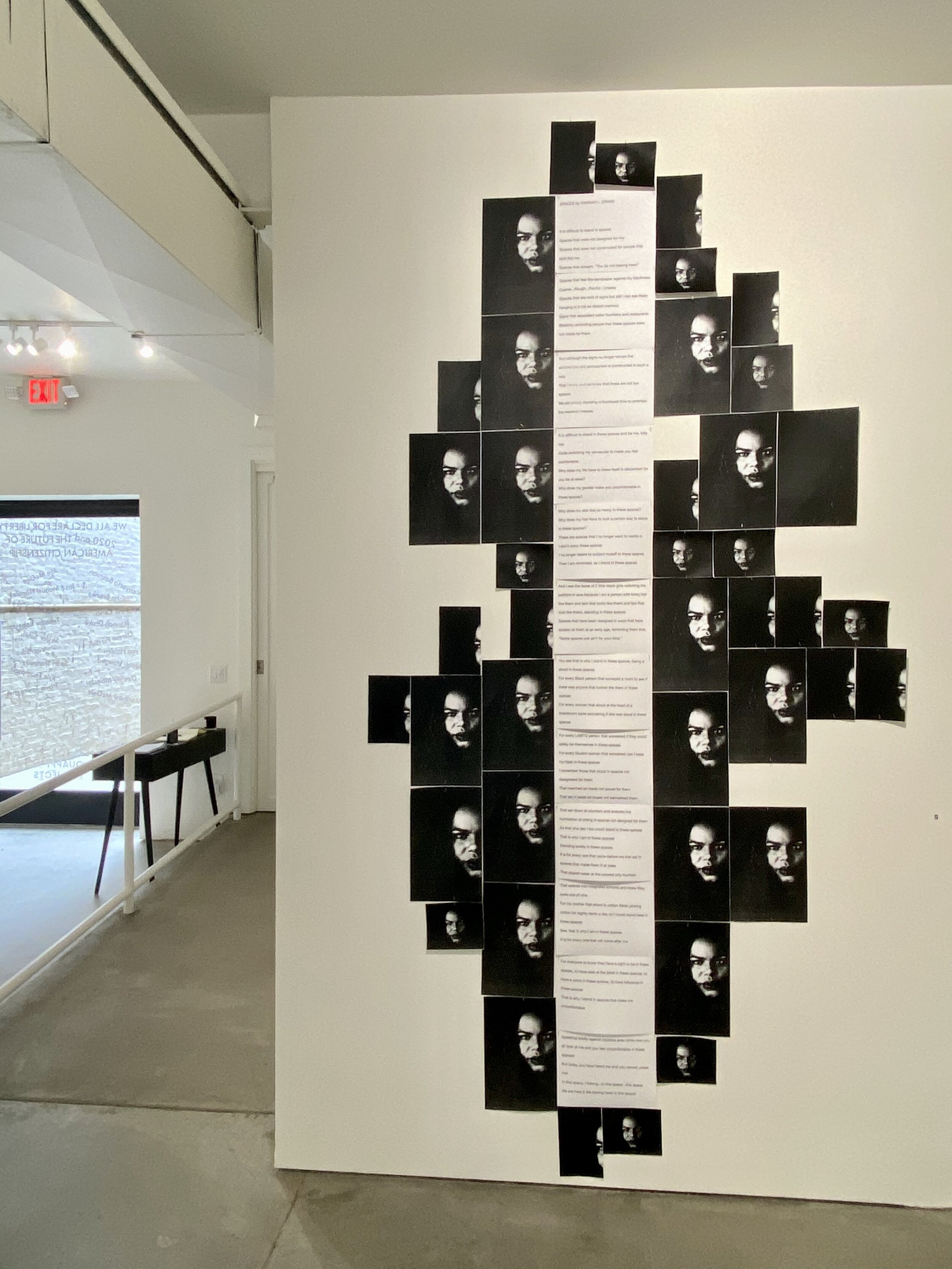

Poet Hannah Drake says “I am writing to shake a nation.” She is a force for change - not just in Louisville, but around the country and, having recently been published in London’s The Guardian, increasingly around the world. While not a visual artist, Drake is part of this city’s artistic community. As the year unfolded and the nation’s attention turned to Louisville in the wake of Breonna Taylor’s death at the hands of the LMPD, it felt wrong to put on this exhibition without adding Drake’s voice. Spaces is one of her most popular and requested poems. Her finely crafted words speak to her experience and resonate with those who have been - and still are being - othered. What does it say about our nation that in the twenty-first century a Black woman claiming space is still seen as a radical act?

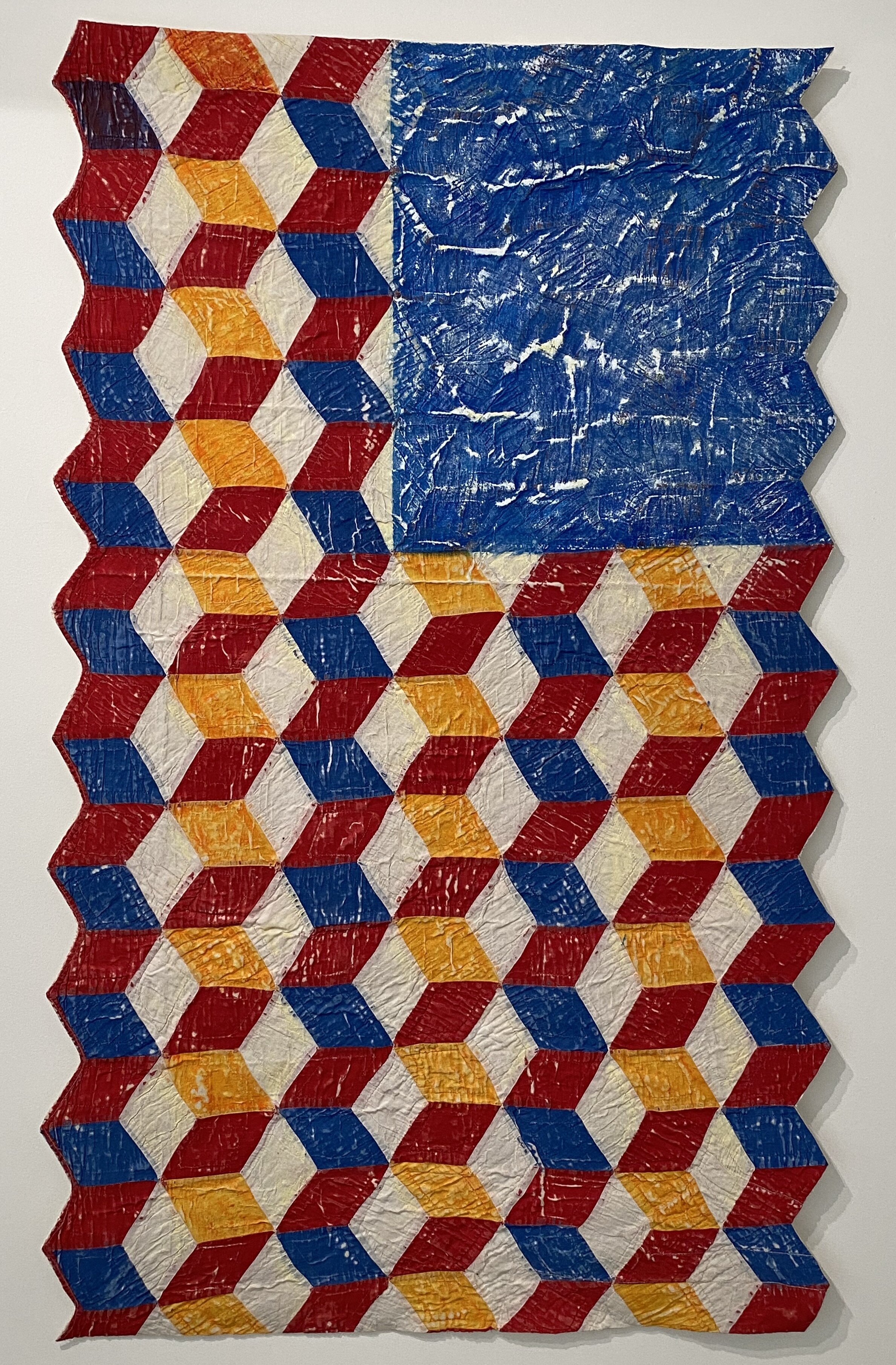

Denise Furnish’s practice primarily consists of repurposing discarded quilts as a way to recognize both the work of women and the objects’ inherent material value as repositories for history. Duplicity utilizes a traditional quilt pattern known as Tumbling Blocks to create an abstracted representation of the American flag. This pattern, which is also known as Heavenly Stairs and Pandora’s Box, causes visual dissonance or an optical illusion. The American flag is a symbol we all know by heart and one that we are taught to revere, yet over the last few years many of us have felt that the ground beneath our feet is shifting, that what we see cannot be trusted, that what we thought we knew of ourselves seems to no longer be accurate. Furnish asks: What does our country stand for? What is truth? Who decides? And this symbol of ours - this symbol of us - is it one of hope or distress?

When the concept for this exhibition was forming in September of last year, no one could have imagined that 2020 would bring the avalanche of crises that it has. By any measure it has been an unprecedentedly formidable year - and it is not yet over. Many Americans feel suddenly caught in the currents of history, farther from shore than we realized. Between the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic shutdown, the fight for racial justice in the wake of the senseless deaths of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery (and so many others over the course of our nation’s history!), the western wildfires, and President Trump’s impeachment - to name but a few things - it could not be more clear that art, let alone life, does not exist separately from the events and movements of society, culture, and politics. What happens in government matters. And in a republic like ours, what happens in government is supposed to be a reflection of citizens’ wishes, yet polls show that Americans feel disconnected from and helpless to affect the machinations of their government. This is a scenario that is ultimately not sustainable. The health of a nation is dependent upon the actions and engagement of its citizens; therefore, to participate in one's citizenship is not a neutral act. Likewise, neither these artists nor their work is neutral. There was no intention to make this exhibition partisan, despite it being the case that there is much direct criticism of Donald Trump and his administration. Instead, what this consistent criticism shows is Trump’s outsized influence on the lives of tens of millions of people both in the U.S. and around the world - he is the proverbial elephant in the room. There is little catharsis in these criticisms. These artists, like most people, want to be happy, but they are sick of the state of things, sick of what they see as a complete dearth of national leadership. People are unsettled, fearful in ways unimaginable a few years ago, and they don't know what to do with their rage. It is difficult not to be destabilized by all of this. These artists’ critiques come not from a place of blind prejudice or hatred but rather from a place of love of their country, a place of hope for what it could be, that the United States might one day live up to its ideals; in a word, patriotism. Ultimately, none of this is about Trump. It is about us.

- John Brooks